|

|

On this page you can find

some of the answers for the questions of the exam; in some cases,

the answers are not complete, since you should be able to work them

out for yourselves—but the hints given here should tell you

just what would be an appropriate answer and what would not be. All

questions were equal in value and the best 6 questions you answered

were counted into the final grade.

| Q1 |

This question is about what you can do with a

particular grammar. The grammar is given for the question and

so you should not change it. You should only change a grammar

in a question if you are explicitly told do.

(a) there is only one rule that illustrates direct recursion,

that is, a rule that has on its righthand side an occurence

(in brackets or not) of the symbol that occurs on the lefthand

side, and that is rule (ii). Recursion is also created indirectly

by going from NP to PP and within PP to NP, but that is not

direct recursion.

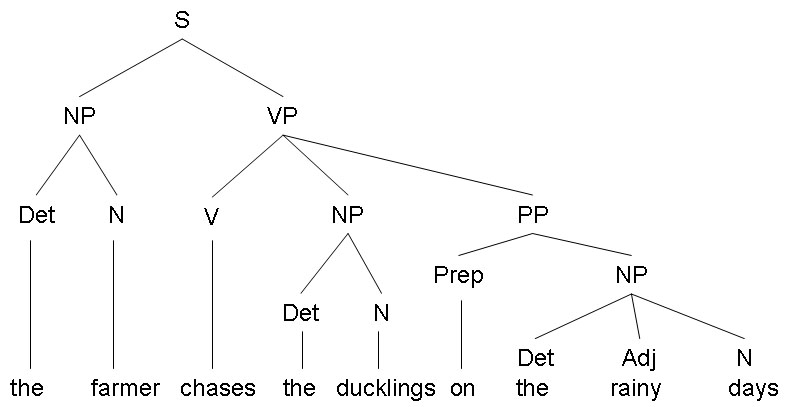

(b) The example sentence: "On rainy days the farmer chases

the ducklings" obviously cannot be generated with the given

grammar as it begins with a prepositional phrase and there is

no combination of rules in the grammar that can lead to a prepositional

phrase being at the front.

If you attempt to create a sentence that is closest to the

given one ideationally, this means that you are not allowed

to change the Process, Participants and Circumstances. The only

way you can do this is by changing the word order, so the prepositional

phrase 'On rainy days' has to move. Note that the grammar is

also not able to produce 'on rainy days', because the Determiner

is obligatory in the NP rule. This is OK in that it does not

change the ideational meaning particularly but you would need

to make this change for full marks here. The grammar does not

produce 'on rainy days' and you should not change it. This gives

the sentence "The farmer chases the ducklings on the rainy

days".

If we put the PP at the end of the sentence, then there are

two syntactic trees that the given grammar can produce to cover

the sentence (this is then one answer to part (d) of this question).

Only one of these is appropriate as an answer

to this question however, since only one of these would have

the prepositional phrase as a Circumstance. This is the tree

shown here:

The other tree (see part (d) below) is not possible as a representation

of this sentence. This is because it puts the PP underneath

the NP 'the duckling'. It is not then a Circumstance but a modifier

of the duckling. Grammatically and semantically this has completely

different consequences (e.g., try passivising).

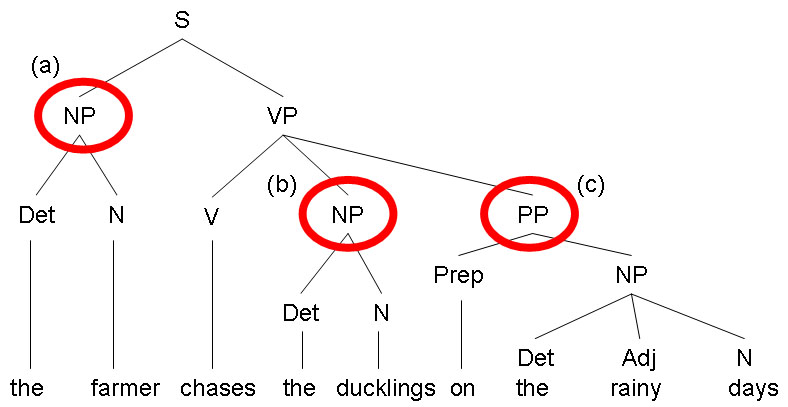

(c) You are asked to circle nodes in the tree,

not the words, that correspond to the Subject, Direct Object

and any Circumstances. This is to show that you know what the

tree has to do with the Subject, Direct Object, etc. It is not

enough just to be able to recognise these in the sentence. The

nodes that you have to circle are the [S, NP], i.e., the NP

child node of the S, [VP, NP] and [VP, PP]. This looks as follows:

Note that both of the following answers are wrong:

you should know why.

(d) The trees above already show an example of structural ambiguity.

This is where you have the same string of words

but different trees built on top of them. All the trees have

to be allowed by the grammar of course. |

| Q2 |

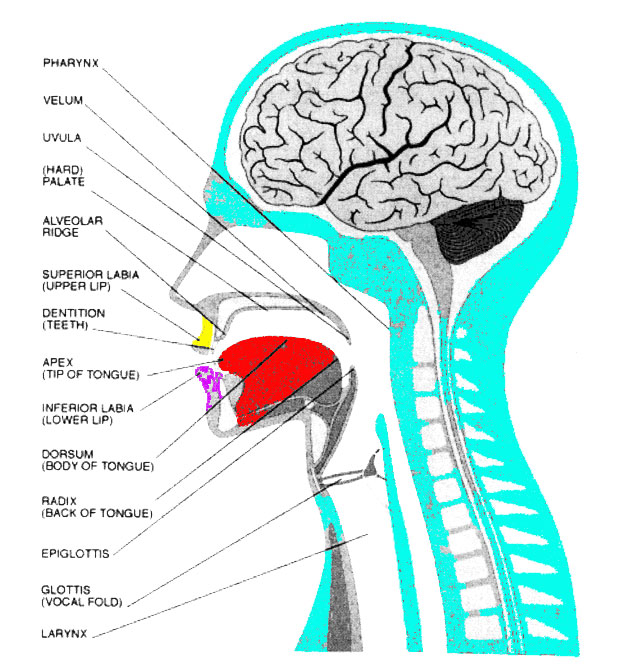

(a)  (click for larger view)

(click for larger view)

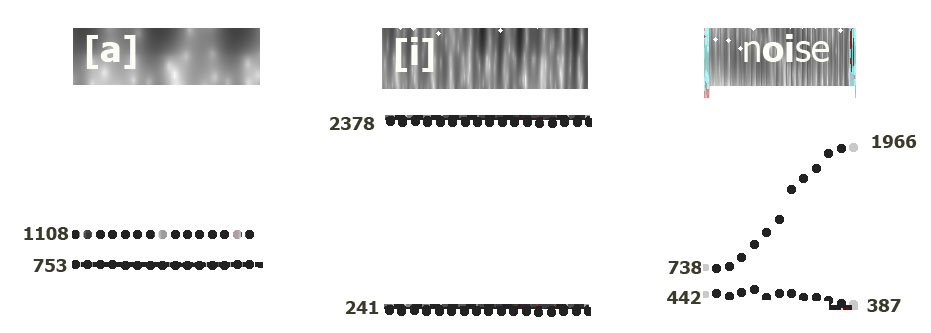

(b) This question is about formants and acoustic phonetics.

Each vowel has two formants: therefore all answers that just

drew some single line for a vowel were completely wrong. For

each vowel you need to show their two formants. Important here

was to show their relationship to each other, not their precise

values. The dipthong in 'noise' of course needs then four results,

the two formants for the beginning of the vowel and the two

formants at the end of the vowel. This looks as follows:

The pure tone is of course just a single straight line, way

below any of the vowel formants. You should

now be able to work out exactly why these patterns come out,

given your notes on phonetics.

(c) The fundamental frequency is the sound made by the vibrating

vocal chords. The fundamental frequencies important for distinguishing

vowels are created by the shape of the mouth, i.e., where you

put the tongue: since that is how you change vowels.

|

| Q3 |

Important here is both to show you know what allophones

and allomorphs are and why they both work quite differently from

each other. Most people remembered that, for example, the phoneme

'l' in English has two common allophones, the clear l and the

dark l, pronounced in different parts of the mouth. For full marks

here you should also have said something about just when one can

occur and when the other can occur. Also many people remembered

that the plural morpheme in English can be expressed phonetically

by an -s, a -z, or an -iz sound. Again for full marks you should

have said something about just when one can occur rather than

the other. Then you could say something about the important difference

between allophones and allomorphs and why we need both. The conditions

for choosing an allophone depend on the phonetic context; the

conditions for choosing between the plural allophones

depend on the fact that a particular morpheme is being expressed.

This cannot be captured purely in terms of phonetics

and so demonstrates that we need allomorphs too, if we are going

to explain what is going on. |

| Q4 |

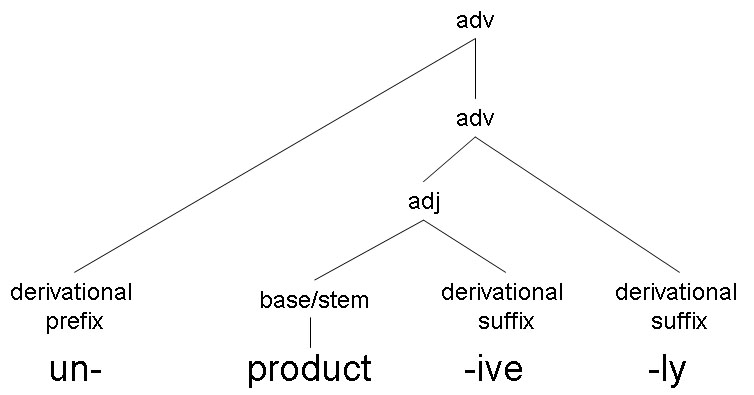

One possible analysis would be the following:

Others are possible, but not any that contain impossible words,

like an 'unproduct'. Note that we might also consider taking

'product' apart, perhaps from 'produce' as verb and some derivational

affix that turns this verb into a noun 't', although this is

not a very productive suffix... All of these affixes are derivational,

because they are not simply indicating grammatical modifications

but are actually changing the word. |

| Q5 |

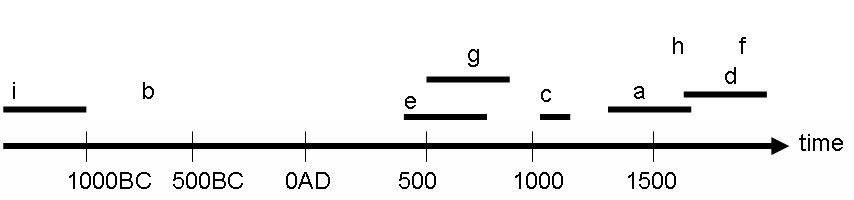

This was a very easy way to get marks: the dates

did not have to be extremely accurate (apart from the few cases

where there is some easy historical event to latch on to). More

important was getting them in the right order and more or less

into the right centuries or time frame. This would look something

like:

|

| Q6 |

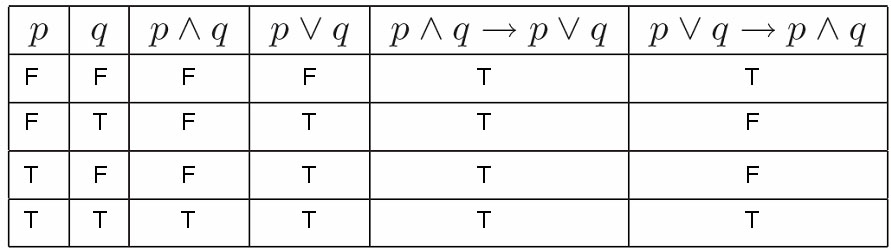

Also an easy way to get points, just filling

in the truthtable as follows:

The observations that you should make here are the fact that

the first implication is always true (a tautology) regardless

of what p and q are, and in the second case the implication

is only true when p and q are identical (i.e., both true or

both false). This latter is then equivalent to an arrow pointing

both ways between p and q. You got partial marks for getting

any of the ands, ors and implications correct systematically;

if there was not recogniseable pattern, then you did not. |

| Q7 |

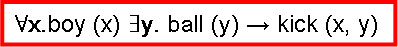

In the two parts of this question, in the first

you just had to show that you could put together the pieces

of logical formula in order to get some appropriate representation

for the given sentence; in the second part, you had to go further

and show how you could use the syntactic tree as a series of

instructions for how to put together a logical expression: i.e.,

to show compositional semantics in action.

An answer for part one would therefore be something like:

You got a few extra marks if you commented on possible ambiguity,

if you showed that you new what higher and lower scope are,

and if you also knew what scope and ambiguity have to do with

each other.

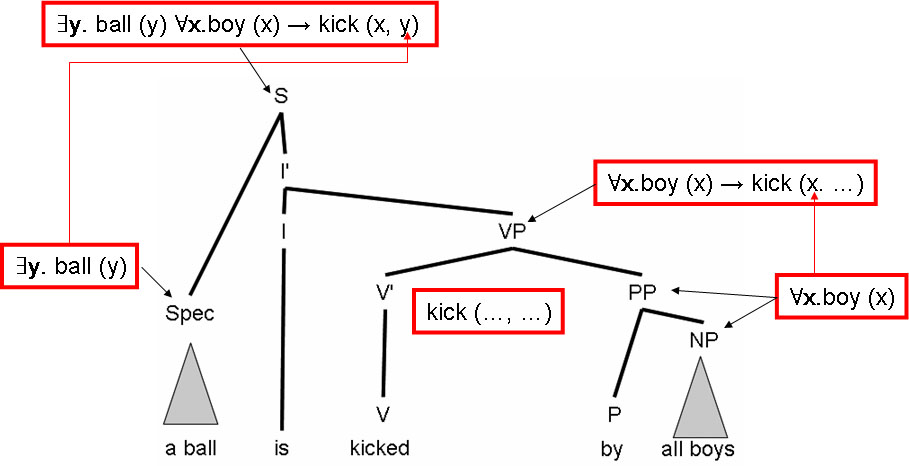

For the second part, you need to show some connection between

the tree and the growth of the logical form. That would loke

something like:

Here you can see exactly what semantics is associated with

each node in the tree, which is the point of the question. You

got marks if you showed you knew what the individual nodes meant,

and even more marks if you could express this using logic. |

| Q8 |

You should have used the standard definitions of

the terms as given in the reading and class, and knew how these

correspond to logical forms. You obtained marks when these were

applied sensibly: i.e., it was clear you knew what you were writing.

A good example of where some of you were not

clear about what you were writing was when it was not only claimed

that mother-father were converses but the correct

logical form for converses was given. The correct logical form

for converse is P(x,y) <-> Q(y,x). So if you wrote something

like father(x,y) <-> mother(y,x) [as some of you did], you

must also think what does that mean. It means

that you are suggesting that if you are someone's father then

that person is your mother. This is obviously absurd: so, as always,

it is never enough just to write some analysis down (semantic,

syntactic, etc.), you must know what consequences follow

from what you write!!! |

| Q9 |

The correct answers are as follows, with the

following code: Subjects, Participants,

Processes, Circumstances.

- The man in the moon

jumped over the fence

- Once upon a time there

was an old pin

- Sitting around in exams

is dangerous to the health

- On Tuesdays she

used to do yoga.

In addition, 'sitting aoound in exams' is also a clause, consisting

of the following functional constituents:

Subjects, participants, processes and circumstances are all

functional constituents of clauses and only clauses!

This means, for example, that the 'in the moon' in

the first sentence can never be a circumstance

in English: that is not what the sentence means. If you are

not clear about this, make sure you become clear (Sprachpraxis!).

The ambiguities for the second part of the question are as

follows:

- The bad man was given [the book on the table by his

mother].

- The bad man was given the book on

the table by his mother.

- The bad man was given [the book on the table] [by

his mother].

- The bad man was given [the book on the table] by

his mother.

Any more?! |

| Q10 |

This was also straightforward: you had simply to

see what sound changes were occuring in the data on the right

of the question, and to pull out of this a generalisation that

covered all the changes. There were two conditions, one for voiced

plosives (e.g., b and g), and one for unvoiced plosives (k, t).

The fromer loose their voicing, the latter lose their plosiveness

and become fricatives. This is all you needed to write. Further

interpretations in terms of Grimm or anybody else were not necessary.

Since the asked about sound [p] is an unvoiced plosive, you needed

to say that what happens is that after this you have an unvoiced

fricative, preferably a bilabial fricative, but as long as you

got the general direction of the change right, I was not too fussy

(so [f] was also OK for example). |

| Q11 |

For this question the main point was to see if

you could apply what we saw in class and had in the readings to

some data. This again means thinking and not just trying to fit

some text that you have learnt. It also required looking at the

data rather than imposing your presuppositions. Clearly the data

do not represent any known standard variety of English because

the more 'prestigious' form is the one with the glottal stop.

We know this because this is the direction of correction for all

areas examined. This is compatible with area C being the highest

social class. Those of you who put it the other way round were

just not applying what we have learnt and were ignoring the data,

always a good way to get very bad analyses and to miss what is

going on. Those of you who also talked about the special cross-over

role of the middle classes (which is also evident in the data,

because this is where the greated correction occurs) obtained

extra marks. |

|